It was a game that should not have been played, a game that was more about the field than what happened on it. The field for at least one night was haunted, maybe because Halloween had something to do with it. Most likely a three-day blow of incessant rain had left Wheeling Island Football Field with a battered stucco surface.

Back in 1970, five Wheeling high school teams –Triadelphia, Warwood, Linsly Military Academy, Wheeling Catholic Central and Wheeling—called the island stadium home, not to mention their freshman and junior varsity squads. Multiply five by the games that were played nine weeks into the West Virginia season and the result was a field trampled by a constant stampede of human beef.

Then came Halloween on Saturday and Mother Nature turned into a mischievous witch wearing Linsly colors and cast a spell at the Mischief Hour of 12 pm and ceased the rain, leaving time enough to dry the field into clay with a texture of Play Doh.

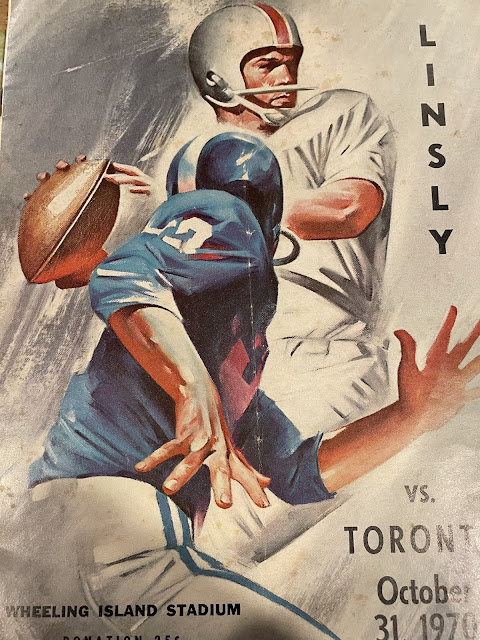

There had been some concern the upcoming football game between the Toronto Red Knights and the Linsly Military Cadets would be canceled because of flooding. A win would continue the Red Knights’ quest to become the team with the second greatest win-loss record in school history with a 9-1 season.

|

| Senior Center Ron Paris |

By the time visiting Toronto disembarked from the school bus, the first thing most players noticed was that the only grass remaining on the field were four little triangles in the rear corners of the end zones. A few fragments of chalk lines somewhat suggested a hint of former occupancy by some organized entities. The field did have a surreal Zen-like quality; you could see the reflections of the floodlights in a thousand or so mini-puddles.

The opening kickoff pretty much summed up the game for the visitors. Red Knight return man Bob Morris collected the ball somewhere around the 20 and scooted downfield 40 yards, unfortunately the last 30 were out of bounds.

“I thought I was going to go all the way,” said Morris, a longtime football coach and an inductee in the Toronto High School Athletic Hall of Fame. “But I guess I was a tad out of bounds.”

The uncharted runback by the 1971 THS graduate turned out to be the longest play of this Halloween eve for the Red Knights. They would not gain a first down until the fourth quarter. Linsly would gain four first downs, all on runs more than ten yards. Besides those four runs, the Cadets pretty much went backward in yardage the remainder of the game.

|

| Bob Morris posing in the Red Knight 1970 program |

“I remember the DB guarding me, his name was Tom Tribett,” Morris said. “I remember telling him after the first few minutes of the game, ‘Let’s not get in this shit if we don’t have to.’ Well, by the end of the first quarter, you couldn’t tell who was or who wasn’t on your team.”

“We changed jerseys at halftime,” said quarterback Bob Eshbaugh, another THS 1971 grad and Hall of Fame inductee. “I wasn’t worried about getting the ball from center but getting my feet out of the mud. It had suction and was up to my shins.”

The ball was on the ground more than in the air, courtesy of 14 fumbles to 11 forward passes. Had the sport been baseball, the ball would have been illegal because of the aerial tricks a doctored ball could do. The only tricks during this game were sleight of hand-- now you have it now you don’t-- as exhibited on the first drive of the game when center Ron Paris long snapped a ball that stuck in the mud three feet behind him. On film, it looked like the senior snapper laid an egg, which Linsly promptly collected.

“I remember,” Morris said, “someone lost his shoe in the mud on the field and during the game the refs took the football to the faucet on the stadium wall and just hosed the mud off the football.”

Toronto outweighed the host team by 20 to 25 pounds a man. Usually on a wet surface, the heavier team holds a big advantage, but in this kind of quicksand, the lighter team simply doesn’t sink as deep.

At 6’ ½” and 202 pounds, senior Red Knight Tom Lowery was the second heaviest player on the field that evening, two pounds lighter than fellow tackle Ted Butler. “It was terrible conditions that night,” Lowery said. “You couldn’t do anything on that slop. I remember looking at Ted Butler after we made a tackle and all I could see was his eyes with that mud all over him. It was funny as hell.”

Remarkedly, there were zero penalties called on either team. The closest any infraction that could have been called was the opening kickoff when the Cadets gang- tackled Morris five feet out of bounds. Had an ineligible lineman went out for a pass, the referees wouldn’t have known it. Of course, getting the ball to any receiver was the problem. By the fourth quarter the ball was as heavy as an anvil. “I had to shotput the ball,” Eshbaugh said about his passing form.

In the fourth quarter,” Toronto and Linsly squared up with a goal line offence versus a goal line defense with the Toronto offense utilizing running back Jim Franke. Franke’s flatfooted style proved him to be what they call in horse track lingo a mudder. Behind a seven-man front and full-house backfield, he and Steve Jones ploughed for four consecutive first downs to the Cadets’ 12-yard line. But the Knights could push no farther because, unfortunately, for both teams this was the worst end of the field regarding game conditions. Compared to the other end, which still had some traces of chalk lines, this end of the field more resembled land recently washed by a receding flood. The Cadets fumbled the ball right back to the Red Knights. Again, Toronto could not wallow beyond the 12. And Linsly promptly coughed up the anvil back to Toronto. On a final desperate attempt to scramble open to get a shotput off toward the end zone, Eshbaugh slipped to the floodplain while trying to change direction, ending the game tied at zero.

“We took our showers with our uniforms on,” Eshbaugh said.

“I remember getting hosed down with water after the game to get the mud off and having your shoe strings cut so you could get them off,” Morris said.

Summing up the game, Morris said, “The line couldn’t get any footing, receivers couldn’t run routes and running backs couldn’t run. Everything seemed to be in slow motion.”

Toronto experienced only one injury and that didn’t occur until after the season when two-way senior Bill Sloane missed the first part of basketball season because of blood poisoning, his condition attributed to the mud from Wheeling Island Stadium.

“We should have never played on the field,” Morris said. “We had a good team and would have crushed them on a dry field. I know Coach (Wilinski) was hot about the field and game, and we never played Linsly for a long time after that.”

“All I know is we would have killed Linsly on a dry field,” Lowry said. “Wellsville beat them 50-0 on a dry field.”

Wellsville was the only team to beat Toronto that year by six points in another freakish game. After the Mud Bowl, the Red Knights defeated their next two opponents by a combined 92-18 points to finish the season with still the second greatest school record at 8-1-1.

I am not so sure we would have blown them out on a dry field," said Bob Petras, a two-way senior lineman. "Defenses that lined up in a 52 always gave us problems on offense. Carrollton, J.U. and Linsly manned 50 alignments with a middle guard, which eliminated our trapping the tackles and made pulling around the opposite ends slower, and those were our bread-and-butter plays. Still we should have beaten Linsly by two, three scores. Like the Wellsville game, when we suffered injuries and illness and lost Eshbaugh to ejection, the Mud Bowl, 50-some years later, still haunts me. We were so so close to having a perfect season."

CHECKEYE